Give me color:

forgotten fictions of interraciality, 1950-1967

The conventional narrative about early Cold War film is striking in its simplicity. In an effort to symbolically integrate the newly adrift populations of a decolonizing Third World, the story goes, both the United States and the Soviet Union turned to film. Political and economic collaboration alone could not secure alignment. Political ideologies needed to be sold in an increasingly competitive marketplace, and cultural diplomacy and ambassadorship became de rigeur. But in addition to selling the nation through media, each country also seized the other’s media output as a handy tool for criticism.

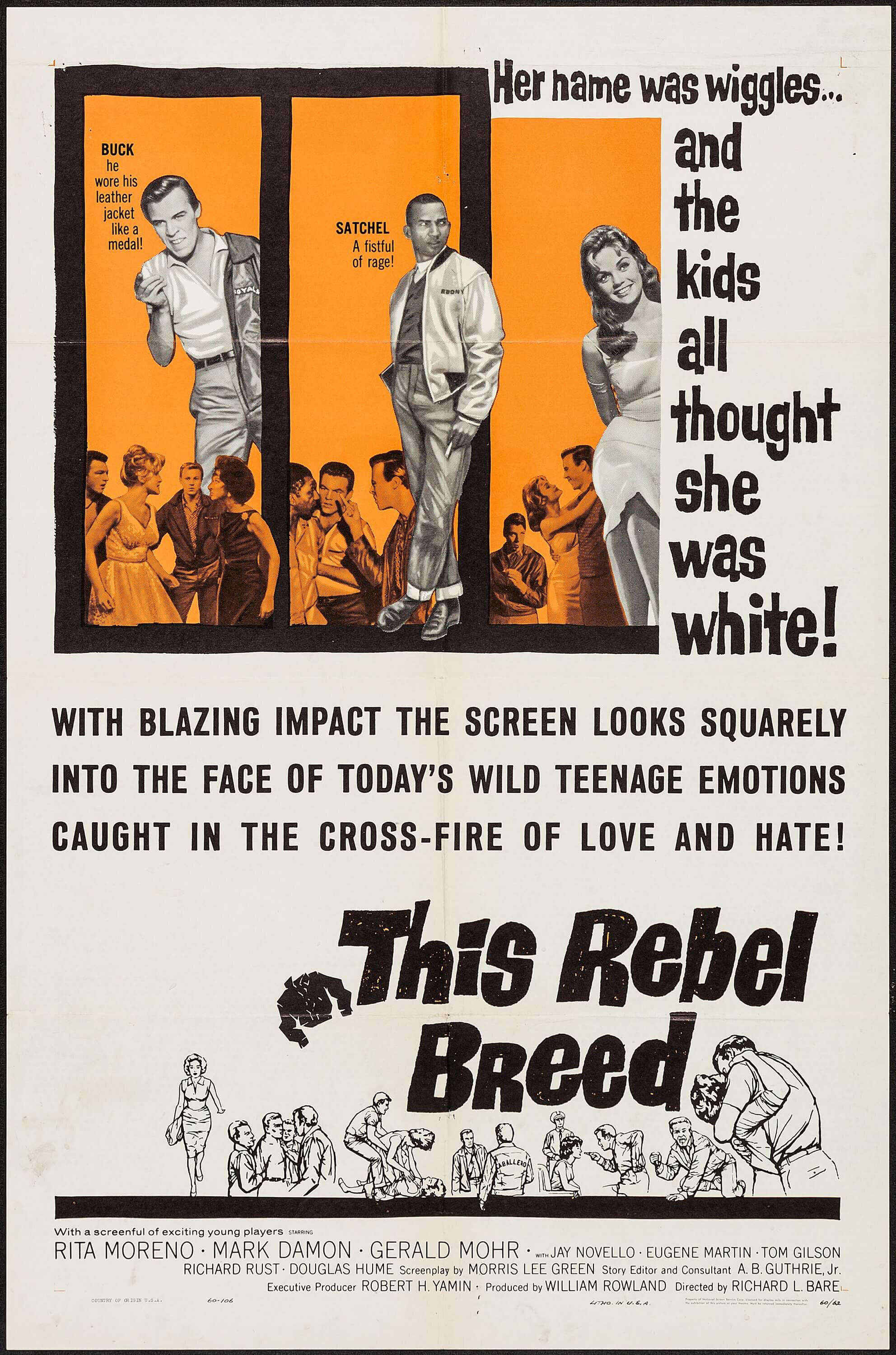

When it came to race, the United States was easy to criticize. “Hollywood acts instead of lynch law, and together with lynch law,” the Soviet Ministry of Culture provoked. In response, at a set of highly-publicized Senate hearings in 1953, policymakers debated how to enlist Hollywood to positively impact the image of the US overseas. The result, eventually, was a slew of films featuring interracial romances, fictions of interraciality that began to symbolically suture the frayed U.S. racial landscape and image abroad. Film, in this narrative, joined hands with U.S. foreign policy objectives, and any productions that jeopardized these goals fell victim to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). The films that survive and that have been canonized from this time period corroborate this narrative; from The King and I to West Side Story, on screen there was no ethnic, racial, or national difference that could not be healed through romance.

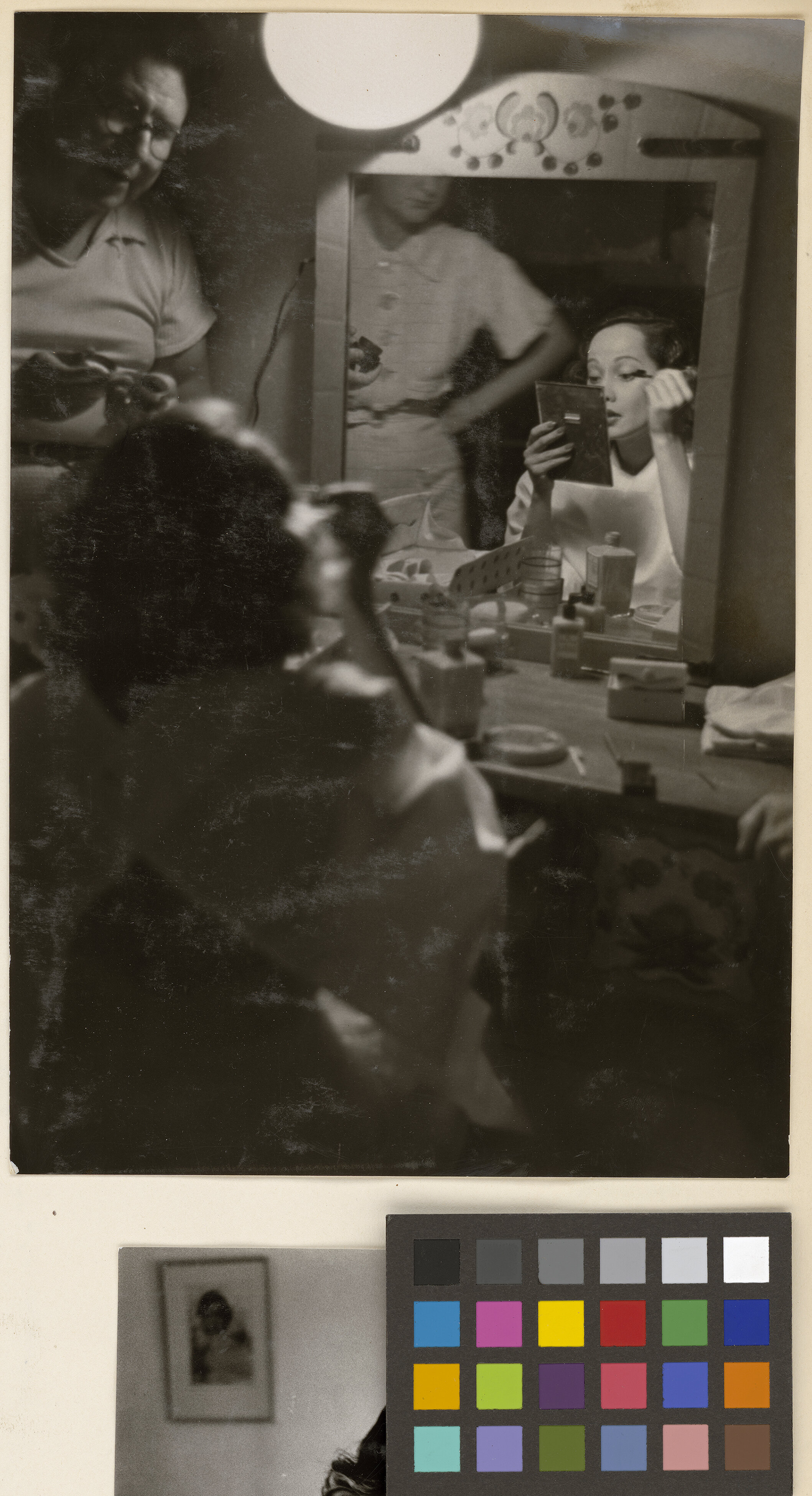

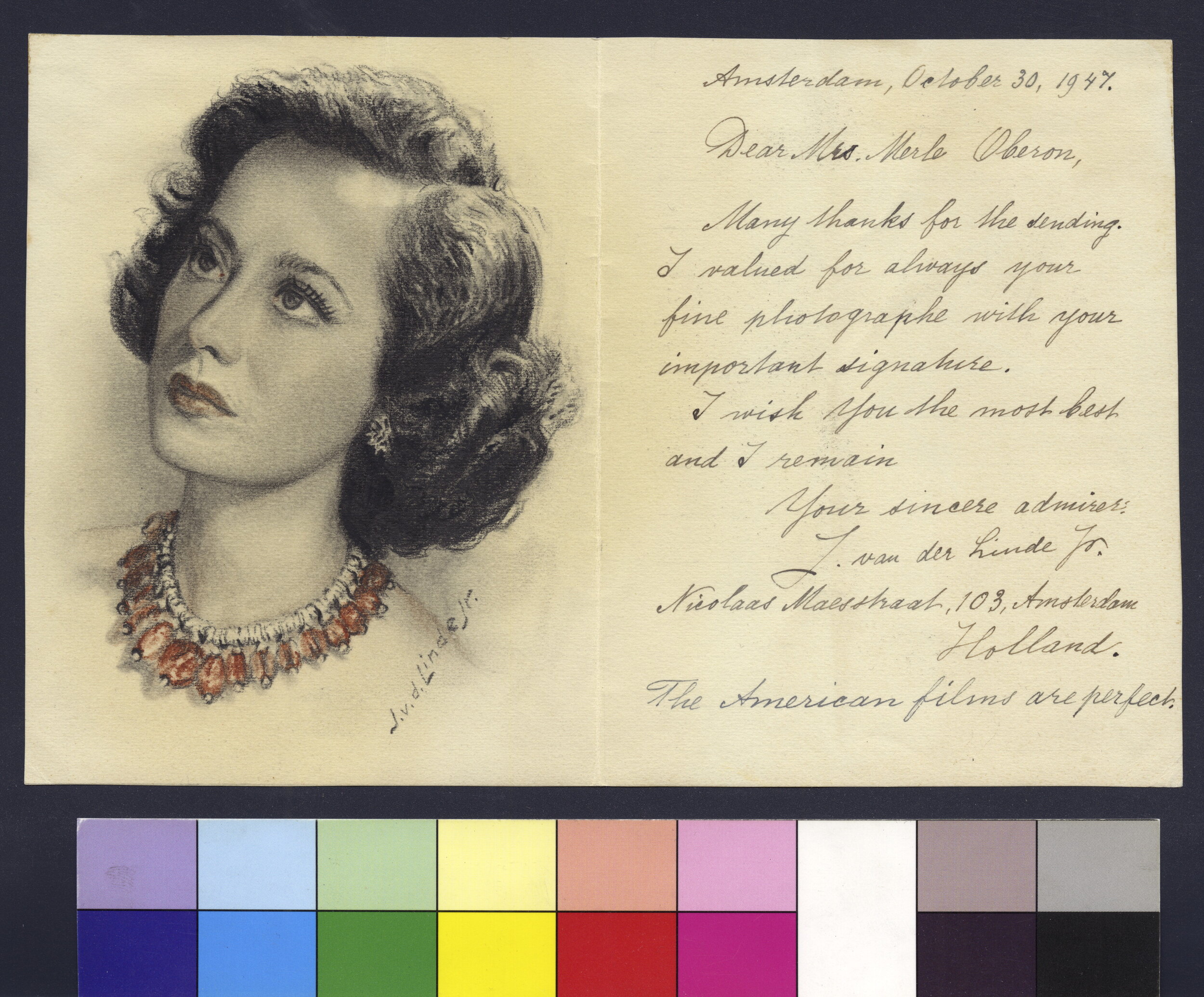

As I show in Give Me Color, however, this narrative is also incomplete, so incomplete that it warps our understanding of the historical record. Give Me Color begins where previous texts have ended. I rigorously engage with the popular interracial romance features of the time, but instead of reading their surface narratives as merely sentimental, orientalist, or propagandistic, I show that they also represent a new stage in cinematic representation: that of the ambiguously racialized woman on screen. What, I ask, comes into vision when we do not merely train our eye on the individual storylines themselves, but instead take a bird’s eye view of the entire genre of interracial romance instead? That figure, I answer, of the racialized actress across type, wielded along the political spectrum. Specifically, Give Me Color reveals that between 1950-1967, the presence of women of color on screen increased dramatically, even as these same women occupied roles that were racially unconventional, mixed, and difficult to pin down. This was especially true for leading roles. Rita Moreno, Nancy Kwan, Dorothy Dandridge all starred in a number of films that broke new ground for racial representation on screen, and that refused racial convention. Why and how did this happen? Who made it happen? And, given the political context, what purpose did it serve?